This post was originally published on January 28, 2015.

What if you could turn smartphones or iPods into a streaming cameras, then get a look at what other people doing the same thing were streaming worldwide? That was the idea behind KooZoo, an iPhone app meant to utilize the “old” technology that inevitably hangs around after new devices are purchased. But KooZoo and similar camera apps pose a worrying question: Where's the line between public and private information?

Out of the cage

According to The Verge, the idea for KooZoo came from former sales exec Drew Sechrist. While on vacation in 2008, he got homesick for San Francisco and started thinking about a way to see what was going on back home — and not just in the city at large but his house specifically or the coffee shop around the corner. While webcams and security systems were one possibility, both were expensive and could be complicated to set up. That's when he hit on the idea of taking old iDevices and turning them into streaming cameras that people could use to record anything, anywhere.

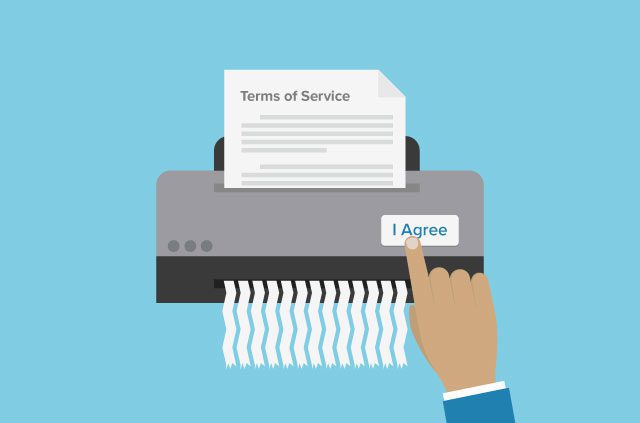

Here's how it was supposed to go: Users download the app and then set up an account, after which they can start streaming video — which they can choose to make public. Unless someone is actively watching a feed, it stops taking video and instead grabs a snapshot every few minutes; this saves battery life and lowers bandwidth consumption. Of course, this kind of service presents a number of problems; most notably privacy. It is possible to ensure that recordings are only of public spaces and aren't illegal in any way? Services like Instagram and Vine have the same issue, and Sechrist said his plan was to use an “advisory board” of privacy and computer experts to determine what was fair game and what was off-limits.

Sounds scary, right? Well, here's the thing: After making a big splash in early 2013, KooZoo vanished. No Android app ever materialized and the iTunes version is no longer available; the app's Twitter account hasn't made a post in two years. Maybe privacy problems did in the company — though the idea of grabbing specific information about public spaces rather than city-sponsored CCTV was intriguing — but whatever happened, the service didn't catch on. More important than one app, however, is the long game here: Sophisticated apps like this are coming, and come with inherent risk.

Up to no good?

Consider the recent story of a woman from the UK who discovered that her husband was using a tracking app — Cerberus — to monitor not only her activities but those of her children as well. As reported by The Inquisitr, Catharine Higginson first found out that something was going on when she missed a text from her bank about a money transfer. When she got home, her husband told her that he had taken care of it since he could read her texts, determine her GPS location, listen to conversations and even use her camera in real-time to see exactly what she was doing at any given moment. He'd also installed this spyware on the phones of his three stepchildren, giving him almost limitless insight into their daily activities.

Surprisingly, Catharine now claims she's “fine” with the intrusion, since she has nothing to hide. Sound familiar? This is the same logic that governments often use to justify digital snooping — if you're not doing anything wrong, they say, you have nothing to worry about. But apps like Cerberus and the potential hinted at by startups like KooZoo tells a different story: At what point does the line between “doing something wrong” and just “doing something” disappear?

Baby steps

Of course, chances are the move from minimalist surveillance tactics to all-out spying won't happen overnight and won't be on the backs of smart devices alone. According to the Independent, for example, hundreds of video baby monitors and CCTV cameras were recently hacked and their feeds broadcast on a free-for-all website. On a more sinister note, there's the example of Moosa Abd-Ali Ali, an activist whose phone was infected with high-grade spyware called FinFisher after he fled his home country. The spyware gave remote users complete access Moosa's smartphone, giving them the ability to use and compromise any of his applications. FinFisher was removed, but its presence was a clear indication that some government agencies aren't afraid to go the distance when it comes to accessing personal information.

Bottom line? KooZoo isn't a risk because it never got off the ground. But similar apps exist and even more sophisticated versions are in the works. When you're online, there's a chance anything you see or do could be monitored, recorded or exploited — surf safe, protect your interests and maybe find that old iPhone a new home. One “smart” device is risk enough.

Take the first step to protect yourself online. Try ExpressVPN risk-free.

Get ExpressVPN